Prediction Terminology#

Terminology is often confusing and highly variable amongst those that make predictions

in the geoscience community. Here we define some common terms in climate prediction and

how we use them in climpred.

Simulation Design#

Hindcast Ensemble (HindcastEnsemble):

Ensemble members are initialized from a simulation (generally a reconstruction from

reanalysis) or an analysis (representing the current state of the atmosphere, land, and

ocean by assimilation of observations) at initialization dates and integrated for some

lead years [Boer et al., 2016].

Perfect Model Experiment (PerfectModelEnsemble):

Ensemble members are initialized from a control simulation

(PerfectModelEnsemble.add_control()) at randomly chosen

initialization dates and integrated for some lead years [Griffies and Bryan, 1997].

Reconstruction/Assimilation: (HindcastEnsemble.add_observations())

A “reconstruction” is a model solution that uses

observations in some capacity to approximate historical or current conditions of the

atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and/or land. This could be done via a forced simulation,

such as an OMIP run that uses a dynamical ocean/sea ice core with reanalysis forcing

from atmospheric winds. This could also be a fully data assimilative model, which

assimilates observations into the model solution. For weather, subseasonal, and

seasonal predictions, the terms re-analysis and analysis are the terms typically used,

while reconstruction is more commonly used for decadal predictions.

Uninitialized Ensemble: (HindcastEnsemble.add_uninitialized())

In this framework, an uninitialized ensemble is one that

is generated by perturbing initial conditions only at one point in the historical run.

These are generated via micro (round-off error perturbations) or macro (starting from

completely different restart files) methods. Uninitialized ensembles are used to

approximate the magnitude of internal climate variability and to confidently extract

the forced response (ensemble mean) in the climate system. In climpred, we use

uninitialized ensembles as a baseline for how important (reoccurring) initializations

are for lending predictability to the system. Some modeling centers (such as NCAR)

provide a dynamical uninitialized ensemble (the CESM Large Ensemble) along with their

initialized prediction system (the CESM Decadal Prediction Large Ensemble). If this

isn’t available, one can approximate the unintiailized response by bootstrapping a

control simulation.

Forecast Assessment#

Accuracy: The average degree of correspondence between individual pairs of forecasts

and observations [Jolliffe and Stephenson, 2011, Murphy, 1988]. Examples include Mean Absolute Error

(MAE) _mae() and Mean Square Error (MSE)

_mse(). See metrics.

Association: The overall strength of the relationship between individual pairs of

forecasts and observations [Jolliffe and Stephenson, 2011]. The primary measure of association

is the Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC), which can be measured using the Pearson

product-moment correlation _pearson_r() or

Spearman’s Rank correlation _spearman_r(). See

metrics.

(Potential) Predictability: This characterizes the “ability to be predicted” rather than the current “capability to predict.” One estimates this by computing a metric (like the anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC)) between the prediction ensemble and a member (or collection of members) selected as the verification member(s) (in a perfect-model setup) or the reconstruction that initialized it (in a hindcast setup) [Pegion et al., 2019, Meehl et al., 2013].

(Prediction) Skill: (HindcastEnsemble.verify())

This characterizes the current ability of the ensemble

forecasting system to predict the real world. This is derived by computing a metric

between the prediction ensemble and observations, reanalysis, or analysis of the real

world [Pegion et al., 2019, Meehl et al., 2013].

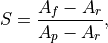

Skill Score: The most generic skill score can be defined as the following Murphy [1988]:

where  ,

,  , and

, and  represent the accuracy of the

forecast being assessed, the accuracy of a perfect forecast, and the accuracy of the

reference forecast (e.g. persistence), respectively [Murphy and Katz, 1985]. Here,

represent the accuracy of the

forecast being assessed, the accuracy of a perfect forecast, and the accuracy of the

reference forecast (e.g. persistence), respectively [Murphy and Katz, 1985]. Here,

represents the improvement in accuracy of the forecasts over the reference

forecasts relative to the total possible improvement in accuracy. They are typically

designed to take a value of 1 for a perfect forecast and 0 for equivalent to the

reference forecast [Jolliffe and Stephenson, 2011].

represents the improvement in accuracy of the forecasts over the reference

forecasts relative to the total possible improvement in accuracy. They are typically

designed to take a value of 1 for a perfect forecast and 0 for equivalent to the

reference forecast [Jolliffe and Stephenson, 2011].

Forecasting#

Hindcast: Retrospective forecasts of the past initialized from a reconstruction integrated forward in time, also called re-forcasts. Depending on the length of time of the integration, external forcings may or may not be included. The longer the integration (e.g. decadal vs. daily), the more important it is to include external forcing [Boer et al., 2016]. Because they represent so-called forecasts over periods that already occurred, their prediction skill can be evaluated.

Prediction: Forecasts initialized from a reconstruction integrated into the future. Depending on the length of time of the integration, external forcings may or may not be included. The longer the integration (e.g. decadal vs. daily), the more important it is to include external forcing [Boer et al., 2016]. Because predictions are made into the future, it is necessary to wait until the forecast occurs before one can quantify the skill of the forecast.

Projection An estimate of the future climate that is dependent on the externally forced climate response, such as anthropogenic greenhouse gases, aerosols, and volcanic eruptions [Meehl et al., 2013].

References#

G. J. Boer, D. M. Smith, C. Cassou, F. Doblas-Reyes, G. Danabasoglu, B. Kirtman, Y. Kushnir, M. Kimoto, G. A. Meehl, R. Msadek, W. A. Mueller, K. E. Taylor, F. Zwiers, M. Rixen, Y. Ruprich-Robert, and R. Eade. The Decadal Climate Prediction Project (DCPP) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev., 9(10):3751–3777, October 2016. doi:10/f89qdf.

S. M. Griffies and K. Bryan. A predictability study of simulated North Atlantic multidecadal variability. Climate Dynamics, 13(7-8):459–487, August 1997. doi:10/ch4kc4.

Ian T. Jolliffe and David B. Stephenson. Forecast Verification: A Practitioner's Guide in Atmospheric Science. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK, December 2011. ISBN 978-1-119-96000-3 978-0-470-66071-3. doi:10.1002/9781119960003.

Gerald A. Meehl, Lisa Goddard, George Boer, Robert Burgman, Grant Branstator, Christophe Cassou, Susanna Corti, Gokhan Danabasoglu, Francisco Doblas-Reyes, Ed Hawkins, Alicia Karspeck, Masahide Kimoto, Arun Kumar, Daniela Matei, Juliette Mignot, Rym Msadek, Antonio Navarra, Holger Pohlmann, Michele Rienecker, Tony Rosati, Edwin Schneider, Doug Smith, Rowan Sutton, Haiyan Teng, Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, Gabriel Vecchi, and Stephen Yeager. Decadal Climate Prediction: An Update from the Trenches. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 95(2):243–267, April 2013. doi:10/f3cvw2.

Allan H Murphy and Richard W Katz. Probability, Statistics, and Decision Making in the Atmospheric Sciences. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1985. ISBN 9780367284336.

Allan H. Murphy. Skill Scores Based on the Mean Square Error and Their Relationships to the Correlation Coefficient. Monthly Weather Review, 116(12):2417–2424, December 1988. doi:10/fc7mxd.

Kathy Pegion, Ben P. Kirtman, Emily Becker, Dan C. Collins, Emerson LaJoie, Robert Burgman, Ray Bell, Timothy DelSole, Dughong Min, Yuejian Zhu, Wei Li, Eric Sinsky, Hong Guan, Jon Gottschalck, E. Joseph Metzger, Neil P Barton, Deepthi Achuthavarier, Jelena Marshak, Randal D. Koster, Hai Lin, Normand Gagnon, Michael Bell, Michael K. Tippett, Andrew W. Robertson, Shan Sun, Stanley G. Benjamin, Benjamin W. Green, Rainer Bleck, and Hyemi Kim. The Subseasonal Experiment (SubX): A Multimodel Subseasonal Prediction Experiment. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 100(10):2043–2060, July 2019. doi:10/ggkt9s.